|

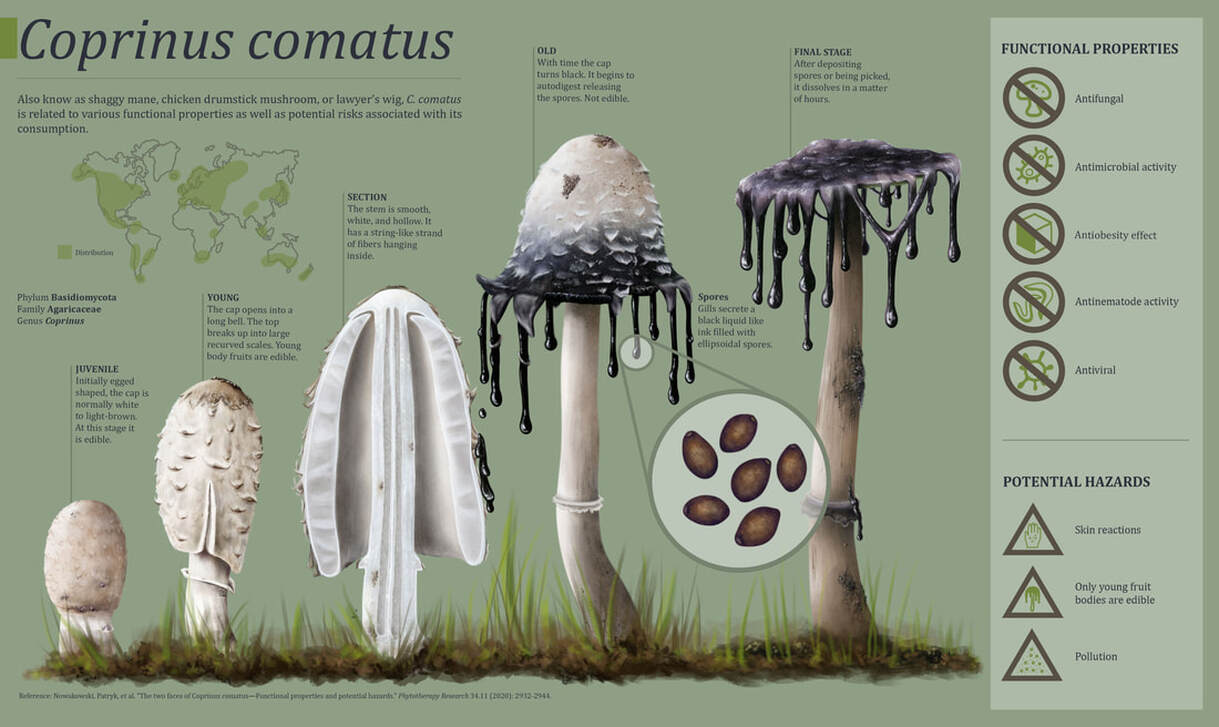

By Cliff Bueno de Mesquita and Ylenia Vimercati Molano Hi everyone! It’s been a long time since our last blog post in January 2021. Today we will revive the blog for October, 2023 with the fascinating edible fungus Coprinus comatus, also known as the “chicken drumstick”, among other nicknames. This fungus is in the Basidiomycota phylum and can be found all over the globe, in all continents except Antarctica (Figure 1). While delicious and nutritious and known for beneficial antioxidant, anticancer, and anti-obesity properties, make sure to only eat young mushrooms, as older ones that start turning black are inedible. As the mushroom gets older, it eventually starts to auto-digest itself. People with atopic dermatitis and atopic predisposition should be wary of consuming C. comatus, as it may cause skin rashes. Younger mushrooms are egg shaped (Figure 1). Even young mushrooms of C. comatus must be consumed, processed, or iced within 4–6 hours of collection [1]. Yet another use of this amazing organism is for what is known as “mycoremediation”, which means remediation using fungi. In particular, several studies have tested the potential of C. comatus to clean up heavy metal contaminated sites, and the results have been quite promising. For example, C. comatus was able to uptake copper and naphthalene (a hydrocarbon found in coal tar and crude oil) out of the soil, which improved the growth of lettuce [3]! Other work has shown potential to uptake copper, lead, cadmium, and chromium [4].

So when people say that fungi are going to help save the world, they are correct, and C. comatus is one specific organism that is making big contributions to our society and the environment. References: 1. Nowakowski P, Naliwajko SK, Markiewicz-Żukowska R, Borawska MH, Socha K. The two faces of Coprinus comatus—Functional properties and potential hazards. Phytother Res 2020; 34: 2932–2944. 2. Luo H, Liu Y, Fang L, Li X, Tang N, Zhang K. Coprinus comatus Damages Nematode Cuticles Mechanically with Spiny Balls and Produces Potent Toxins To Immobilize Nematodes. Appl Environ Microbiol 2007; 73: 3916–3923. 3. Wu B, Chen R, Yao Y, Gao N, Zuo L, Xu H. Mycoremediation potential of Coprinus comatus in soil co-contaminated with copper and naphthalene. RSC Adv 2015; 5: 67524–67531. 4. Dulay R, Pascual A, Constante R, Tiniola R, Areglo J, Arenas M, et al. Growth response and mycoremediation activity of Coprinus comatus on heavy metal contaminated media. Mycosphere 2015; 6: 1–7.

0 Comments

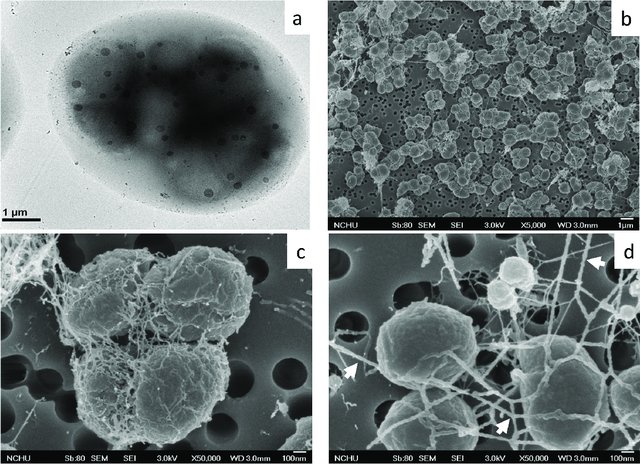

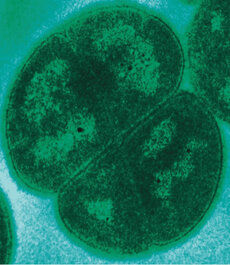

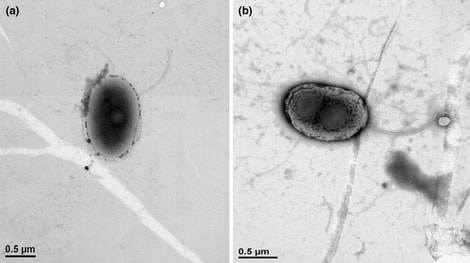

by Cliff Bueno de Mesquita Greetings and happy new year! To kick of the new year, I will continue with the methane cycling theme as I provide some information on the genus Methanolobus. Methanolobus is a genus of archaea in the family Methanosarcinaceae that can perform decomposition in anaerobic (low oxygen) environments. The lack of oxygen causes there to be different chemical reactions when these microbes eat carbon, compared to when, for example, humans eat carbon in the form of food. In anaerobic decomposition, methane is produced from either acetate, carbon dioxide and hydrogen, or various methyl (-- CH3) containing compounds. Generally, the family Methanosarcinaceae and genus Methanolobus are interesting because they are capable of using a variety of compounds and pathways to create methane (Oren, 2014). However, some species of Methanolobus have been reported to grow strictly on methyl compounds such as methanol and trimethylamine (König & Stetter, 1982). They have been found in lakes (Chen et al., 2018) and wetlands (Zhang et al., 2008) as well as a variety of niche environments such as coal seams (Doerfert et al., 2009) and oil wells (Ni & Boone, 1991). A Methanolobus genome was recently isolated from a former industrial salt pond in the San Francisco Bay. Industrial salt production involves creating a pond that is disconnected hydrologically so that water can evaporate and increase the salt concentration. The ponds are shallow and experience high UV radiation and high temperatures. Sadly, the majority of wetlands in the Bay Area were converted to industrial salt production. Even after the salt production stops, these areas can still have really elevated salt concentrations (5 times saltier than the sea!) as well as high sulfate levels. A new study that I’m involved in is reporting elevated methane emissions from these former industrial salt ponds, in part due to the activity of organisms such as Methanolobus. The good news is that efforts to restore these ponds back to their previous natural wetland state can change the microbial composition and lower the methane emissions.  Figure 1. 1. Morphology of Methanolobus strain YSF-03T . (a) The negatively stained cells under transmission electron microscope JEM1400 (JEOL). (b)–(d) Cells under scanning electron microscope JSM-7401F (JEOL). Bars, (a) and (b), 1 µm; (c) and (d), 100 nm. The white arrows indicate the cannula-like structures. From Chen et al. 2018. Methanolobus are halophilic organisms, meaning “salt-loving”. Hence their presence in the former industrial salt ponds where salinity is still high. They’ve also been reported as abundant on hypersaline (super salty!) microbe mats in Baja California (Orphan et al., 2008). Some species can also be considered psychrophilic “cold-loving” (Zhang et al., 2008) but the genus as a whole can grow at a range of temperatures. In our study, the abundance of this organism was positively correlated with methane. We also found mcrA, mcrB, and mcrG genes in its genome which are the genes known to catalyze the final reaction in methanogenesis!

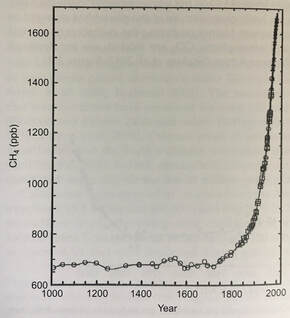

References: Chen, S.-C., Huang, H.-H., Lai, M.-C., Weng, C.-Y., Chiu, H.-H., Tang, S.-L., Rogozin, D. Y., & Degermendzhy, A. G. (2018). Methanolobus psychrotolerans sp. Nov., a psychrotolerant methanoarchaeon isolated from a saline meromictic lake in Siberia. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 68(4), 1378–1383. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijsem.0.002685 Doerfert, S. N., Reichlen, M., Iyer, P., Wang, M., & Ferry, J. G. (2009). Methanolobus zinderi sp. Nov., a methylotrophic methanogen isolated from a deep subsurface coal seam. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 59(5), 1064–1069. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.003772-0 König, H., & Stetter, K. O. (1982). Isolation and characterization of Methanolobus tindarius, sp. Nov., a coccoid methanogen growing only on methanol and methylamines. Zentralblatt Für Bakteriologie Mikrobiologie Und Hygiene: I. Abt. Originale C: Allgemeine, Angewandte Und Ökologische Mikrobiologie, 3(4), 478–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0721-9571(82)80005-7 Ni, S., & Boone, D. R. (1991). Isolation and Characterization of a Dimethyl Sulfide-Degrading Methanogen, Methanolobus siciliae HI350, from an Oil Well, Characterization of M. siciliae T4/MT, and Emendation of M. siciliae. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 41(3), 410–416. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-41-3-410 Oren, A. (2014). The Family Methanosarcinaceae. In E. Rosenberg, E. F. DeLong, S. Lory, E. Stackebrandt, & F. Thompson (Eds.), The Prokaryotes: Other Major Lineages of Bacteria and The Archaea (pp. 259–281). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-38954-2_408 Orphan, V. J., Jahnke, L. L., Embaye, T., Turk, K. A., Pernthaler, A., Summons, R. E., & Marais, D. J. D. (2008). Characterization and spatial distribution of methanogens and methanogenic biosignatures in hypersaline microbial mats of Baja California. Geobiology, 6(4), 376–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4669.2008.00166.x Zhang, G., Jiang, N., Liu, X., & Dong, X. (2008). Methanogenesis from Methanol at Low Temperatures by a Novel Psychrophilic Methanogen, “Methanolobus psychrophilus” sp. Nov., Prevalent in Zoige Wetland of the Tibetan Plateau. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 74(19), 6114–6120. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01146-08 by Cliff Bueno de Mesquita The microbe of this month is the phylum Verstraetearchaeota. Verstraetearchaeota is in the domain Archaea, one of the three domains of life along with the Bacteria and Eukarya. Archaea can be identified with the commonly used 16S gene, although they are often overlooked as 16S studies often focus only on the Bacteria. One of the most important biogeochemical cycles that is dominated by archaea is the methane cycle. Methane is produced by archaea in a process known as methanogenesis which occurs during the decomposition of organic matter in anaerobic (low oxygen) environments. Verstraetearchaeota, along with Euryarchaeota and Bathyarchaeota are the three phyla that contain organisms performing methanogenesis. However, the Verstraetearchaeota were only recently described in 2016 (Vanwonterghem et al., 2016)! Methane (CH4) is a greenhouse gas with a global warming potential 25-35X that of CO2 over a 100-year time span. Methane is produced naturally by methanogenesis in anaerobic environments such as wetlands. It is also produced in the earth’s crust in fossil fuel deposits (i.e. natural gas) and in the guts of some animals known as ruminants (e.g. cows). It is also produced during coal combustion. Human activities and industries have vastly increased the amount of methane released to the atmosphere via landfills and the fossil fuel and animal agriculture industries. Globally, anthropogenic sources contribute about 430 teragrams (1012 grams) of methane while natural sources produce only 215 Tg of methane (Schlesinger & Bernhardt, 2013). This is not surprising when you think about there being over a billion cows on Earth today and they’re all belching methane! And this is one reason, among others, that anyone reading this post should seriously consider going vegan (like two members of our lab!) or at least cut beef and dairy consumption out of their diets! Atmospheric methane levels have risen from around 625 ppb (parts per billion) in the 1700s to 1760 ppb in 2010 (Figure 1). It’s also notable that atmospheric methane levels have never risen above 800 ppb in the last 800,000 years (Schlesinger & Bernhardt, 2013)! Anyways, back to the Verstraetearchaeota. This phylum is cool because its members can perform methylotrophic methanogenesis (production of methane from methyl-containing compounds like methanol), which is one of the three main methanogenesis pathways. The other two are known as acetoclastic methanogenesis (splits acetate into methane and carbon dioxide) and hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis (producing methane and water from carbon dioxide and hydrogen). Acetoclastic and hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis were thought to produce most of the world’s methane, but recently methylotrophic methanogenesis has been shown to be a primary source of methane in some ecosystems, most notably salty environments such as ocean sediments, salt ponds, and coastal wetlands (Conrad, 2020; Zhuang et al., 2016, 2018). Genomic studies have confirmed the presence of genes in Verstraetearchaeota that perform methylotrophic methanogenesis (Vanwonterghem et al., 2016).

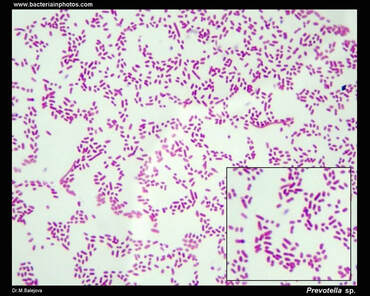

References: Conrad, R. (2020). Importance of hydrogenotrophic, aceticlastic and methylotrophic methanogenesis for methane production in terrestrial, aquatic and other anoxic environments: A mini review. Pedosphere, 30(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1002-0160(18)60052-9 Schlesinger, W. H., & Bernhardt, E. S. (2013). Biogeochemistry: An analysis of global change (3rd Edition). Academic Press. Vanwonterghem, I., Evans, P. N., Parks, D. H., Jensen, P. D., Woodcroft, B. J., Hugenholtz, P., & Tyson, G. W. (2016). Methylotrophic methanogenesis discovered in the archaeal phylum Verstraetearchaeota. Nature Microbiology, 1(12), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.170 Zhuang, G.-C., Elling, F. J., Nigro, L. M., Samarkin, V., Joye, S. B., Teske, A., & Hinrichs, K.-U. (2016). Multiple evidence for methylotrophic methanogenesis as the dominant methanogenic pathway in hypersaline sediments from the Orca Basin, Gulf of Mexico. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 187, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2016.05.005 Zhuang, G.-C., Heuer, V. B., Lazar, C. S., Goldhammer, T., Wendt, J., Samarkin, V. A., Elvert, M., Teske, A. P., Joye, S. B., & Hinrichs, K.-U. (2018). Relative importance of methylotrophic methanogenesis in sediments of the Western Mediterranean Sea. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 224, 171–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2017.12.024 by Cliff Bueno de Mesquita This month I will switch gears and write about a new topic – the gut microbiome. This is not something we are currently researching in the AMO, but is an important subdiscipline in microbial ecology right now with important implications for human health. Many popular media sources in recent years have picked up on gut microbiome research often reporting on how important gut microbes are for human health. This is true and is backed up by a large and growing body of scientific work. But what are the individual organisms? The human gut is dominated by three phyla of bacteria: the Firmicutes (Families Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae), the Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidaceae, Prevotellaceae and Rikenellaceae) and the Actinobacteria (Bifidobacteriaceae and Coriobacteriaceae). These phyla and families are also abundant in the guts of other primates and mammals. One abundant genus is Prevotella, which are Gram-negative bacteria found in the oral, vaginal, and gut microbiota (Figure 1). Prevotella is an important genus to study because it is very abundant in some people and not very abundant in others. In fact, Prevotella was a key taxon driving the idea of “enterotypes” or groupings in humans. In 2011, three enterotypes, dominated by either Bacteroides, Prevotella, or Ruminococcus, were described (1). Prevotella abundance appears to be linked to long-term diet and is more abundant in a plant-based diet compared to a meat-based diet. Prevotella has been linked to diets high in fiber and carbohydrates while Bacteroides to protein and animal fat (2, 3). This makes sense because Prevotella produce enzymes specifically involved in fiber and carbohydrate degradation. A study comparing the gut microbiota in children from Europe eating a typical western diet compared to children in a rural village in Burkina Faso eating a diet high in fiber, similar to early human diets at the birth of agriculture, showed a huge difference in Prevotella abundance, with the Burkina Faso children averaging 53% Prevotella abundance and the European children averaging 0% Prevotella abundance (4). Additional work has found lower counts of Bacteroides in vegans (5). More broadly, chimpanzees have greater abundances of Prevotella than humans.

References: 1. M. Arumugam, J. Raes, E. Pelletier, D. Le Paslier, T. Yamada, D. R. Mende, G. R. Fernandes, J. Tap, T. Bruls, J. M. Batto, M. Bertalan, N. Borruel, F. Casellas, L. Fernandez, L. Gautier, T. Hansen, M. Hattori, T. Hayashi, M. Kleerebezem, K. Kurokawa, M. Leclerc, F. Levenez, C. Manichanh, H. B. Nielsen, T. Nielsen, N. Pons, J. Poulain, J. Qin, T. Sicheritz-Ponten, S. Tims, D. Torrents, E. Ugarte, E. G. Zoetendal, J. Wang, F. Guarner, O. Pedersen, W. M. De Vos, S. Brunak, J. Doré, J. Weissenbach, S. D. Ehrlich, P. Bork, Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 473, 174–180 (2011). 2. G. D. Wu, J. Chen, C. Hoffmann, K. Bittinger, Y. Chen, S. A. Keilbaugh, M. Bewtra, D. Knights, W. A. Walters, R. Knight, R. Sinha, E. Gilroy, K. Gupta, R. Baldassano, L. Nessel, H. Li, Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science (80-. ). 334, 105–109 (2011). 3. A. H. Nishida, H. Ochman, A great-ape view of the gut microbiome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 195–206 (2019). 4. C. De Filippo, D. Cavalieri, M. Di Paola, M. Ramazzotti, J. B. Poullet, S. Massart, S. Collini, G. Pieraccini, P. Lionetti, Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 14691–14696 (2010). 5. J. Zimmer, B. Lange, J. S. Frick, H. Sauer, K. Zimmermann, A. Schwiertz, K. Rusch, S. Klosterhalfen, P. Enck, A vegan or vegetarian diet substantially alters the human colonic faecal microbiota. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 66, 53–60 (2012). We are pleased to share that our paper about our fertilization experiments on Volcán Llullaillaco have been published in the journal Microorganisms (https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8071061) and is openly accessible for everyone. In line with the theme from last month and the theme of microbes that can tolerate extreme environmental conditions, I will write about another radiation resistant bacterial genus – Rubrobacter. This genus was not abundant in soils at our site on Volcán Llullaillaco, but has been found in other dry environments. The Rubrobacter genus was first described in 1988 (Suzuki et al. 1988) and now contains several described species. In contrast to our high elevation field site which experiences freezing temperatures, Rubrobacter has been described as a thermophilic, or heat loving, genus. The genus is also known to be radiation resistant, even to powerful gamma radiation (Ferreira et al. 1999; Chen et al. 2004)! This is notable because gamma radiation is a commonly used sterilization method. Rubrobacter species have been isolated from diverse environments including hot springs (Ferreira et al. 1999; Chen et al. 2004), biofilms on buildings and monuments (Laiz et al. 2009), arid Australian soils (Holmes et al. 2000), and industrial runoff (Carreto et al. 1996). As an example of just how thermophilic some Rubrobacter species are, consider that the optimal growth temperature for Rubrobacter taiwanensis is approximately 60˚C (Chen et al. 2004)! One adaptation that radiation-resistant organisms have is colored pigments. Rubrobacter tolerans (aptly named as it tolerates gamma radiation) contains red pigments identified as the carotenoids bacterioruberin and monoanhydrobacterioruberin (Saito et al. 1994). The interesting thing about these two pigments is that they are common in halophilic, or salt-loving, bacteria.

References: Carreto L, Moore E, Nobre MF, et al. 1996. Rubrobacter xylanophilus sp. nov., a new thermophilic species isolated from a thermally polluted effluent. Int J Syst Bacteriol 46:460–465. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-46-2-460 Chen MY, Wu SH, Lin GH, et al. 2004. Rubrobacter taiwanensis sp. nov., a novel thermophilic, radiation-resistant species isolated from hot springs. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 54:1849–1855. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.63109-0 Ferreira AC, Fernanda · M, Moore NE, et al. 1999. Characterization and radiation resistance of new isolates of Rubrobacter radiotolerans and Rubrobacter xylanophilus Holmes AJ, Bowyer J, Holley MP, et al. 2000. Diverse, yet-to-be-cultured members of the Rubrobacter subdivision of the Actinobacteria are widespread in Australian arid soils. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 33:111–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2000.tb00733.x Laiz L, Miller AZ, Jurado V, et al. 2009. Isolation of five Rubrobacter strains from biodeteriorated monuments. Naturwissenschaften 96:71–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-008-0452-2 Saito T, Terato H, Yamamoto O. 1994. Pigments of Rubrobacter radiotolerans. Arch Microbiol 162:414–421. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00282106 Suzuki K, Collins MD, Iijima E, Komagata K. 1988. Chemotaxonomic characterization of a radiotolerant bacterium, Arthrobacter radiotolerans : Description of Rubrobacter radiotolerans gen. nov., comb. nov. FEMS Microbiol Lett 52:33–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.1988.tb02568.x by Cliff Bueno de Mesquita We (Lara, Cliff, Steve) recently received positive reviews on our manuscript about our project analyzing soil microbial community response to water and nutrient additions on Volcán Llullaillaco, in the Atacama Desert in Chile. One interesting comment from a reviewer was about the bacterial genus Deinococcus. They claimed that it was a typical desert microbe known to be resistant to desiccation and asked if it was present in our dataset. We replied that it was absent to not very abundant in our dataset, perhaps due to the high elevation of our sampling (5,100 meters above sea level) differentiating our site from previous desert samples where it had been found. Our site freezes daily and experiences diurnal freeze-thaw cycles. On the other hand, Deinococcus has been described as a heat tolerant and even heat preferring genus - indeed, in addition to the Atacama, it has been found in other hot deserts, including the Sahara and Sonoran deserts (1). There have been a number of previous studies on this genus or mentioning this genus, and species within the genus appear to be quite fascinating microorganisms! Research in the Atacama Desert, the driest and oldest desert on Earth, has been funded by NASA’s astrobiology program over the past several decades, as it has been described as a Mars analogue (2). Annual average rainfall many parts of the Atacama is less than 2 mm, making it a “hyperarid” desert, even drier than other deserts such as the Gobi and Sahara deserts. Deinococcus is described as being extremely desiccation resistant, having been found in the extremely dry core of the Atacama, living on quartz stones (3). Its presence on rocks also makes these organisms “hypoliths”, literally meaning “under stone”. One cool study found that the species Deinococcus geothermalis was able to withstand temperatures from -25˚C to 60˚C, vacuum, and Mars atmosphere conditions (4)! They are also described as being radiation resistant, and have received some interest for biotechnology applications(5). The genus contains quite a few species (47 have been described). Two of the most well-studied for astrobiology, found in the Atacama Desert, are Deinococcus radiodurans and D. geothermalis. Deinococcus deserti was described in the Sahara Desert. Other species include D. planocerae (6). One study in the Sonoran Desert found nine species and 60 strains of Deinococcus in one soil sample (1)!

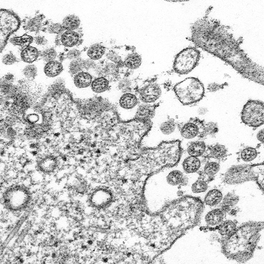

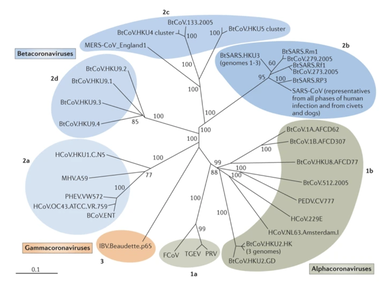

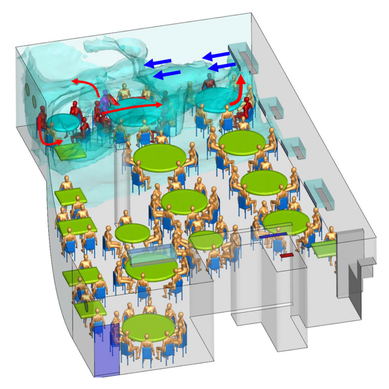

References: 1. Rainey, F. A. et al. Extensive diversity of ionizing-radiation-resistant bacteria recovered from Sonoran Desert soil and description of nine new species of the genus Deinococcus obtained from a single soil sample. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 5225–5235 (2005). 2. Azua-Bustos, A., Urrejola, C. & Vicuña, R. Life at the dry edge: Microorganisms of the Atacama Desert. in FEBS Letters vol. 586 2939–2945 (2012). 3. Lacap, D. C., Warren-Rhodes, K. A., Mckay, C. P. & Pointing, S. B. Cyanobacteria and chloroflexi-dominated hypolithic colonization of quartz at the hyper-arid core of the Atacama Desert, Chile. ExtremophilesExtremophiles 15, 31–38 (2011). 4. Frösler, J., Panitz, C., Wingender, J., Flemming, H.-C. & Rettberg, P. Survival of Deinococcus geothermalis in Biofilms under Desiccation and Simulated Space and Martian Conditions. Astrobiology 17, 431–447 (2017). 5. Sajjad, W. Production and Characterization of Extremolytes from Indigenous Radio-resistant Microorganisms and their Evaluation for Potential Biotechnological Applications. (2017). 6. Lin, H., Wang, Y., Huang, J., Lai, Q. & Xu, Y. Deinococcus planocerae sp. nov., isolated from a marine flatworm. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, Int. J. Gen. Mol. Microbiol. 110, 811–817 (2017). Written by Jacob Bueno de Mesquita Edited by Cliff Bueno de Mesquita For our first microbe of the month on viruses, we give a nod to the current microbial elephant in the room: the causative agent of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, SARS-CoV-2. The main bacterial and fungal players we commonly discuss here are actually much less “micro” than viruses. To give some perspective, a SARS-CoV-2 virion is about 0.12 µm (microns) in diameter, influenza viruses and adenoviruses are about 0.1, and rhinoviruses are about 0.03. A SARS-CoV-2 virion is about 250 times smaller than a human hair, and between 5 and 20 times smaller than an E. coli bacterium. One of the distinguishing characteristics of viruses from other microbes is that they are obligate parasites that rely entirely on hosts to produce proteins for self-assembly. In a sense, viruses could be considered non-living organisms. Perhaps we will dedicate a future post to discussion of the wonders and mysteries of the unique properties of viruses! SARS-CoV-2, like other coronaviruses (CoVs) has a spherical shape, with protein spikes that look like clubs covering its envelope outer surface. These characteristic spike proteins are what give CoVs their name, with some contending the spikes appear like a crown (corona in Latin, Figure 1). The spike protein acts as the virus’s “key” to enter animal host cells, acting as the receptor binding site. Because of its outward presentation and interaction with the host, this is also the protein used as a main target for the rapid vaccine development efforts underway across the globe. The SARS-CoV-2 genome has been studied with extensive phylogeny and transmission chain mapping (Nextstrain). Most virologists and public health experts express gratitude at the Chinese government’s rapid publishing of the genome sequence soon after initial cases emerged in Wuhan. CoVs have positive-sense, single-stranded RNA of 30 kilobases in a single strand (i.e. 30,000 base pairs). This contrasts with influenza viruses that have eight, segmented, negative-sense RNA strands and are more prone to mutation, resulting in the need for seasonal vaccines. Influenza genomic material can get exchanged between the segments when a host cell is infected with multiple viruses (reassortment) and this can lead to new viruses with pathogenic potential. This is one reason that influenza is the “common killer” in humans, remaining just out of the grasp of our ever-evolving immune responses. In contrast, CoVs do not mutate as rapidly, and are generally known for causing common colds. Humans have been carriers of CoVs for hundreds of years (perhaps even thousands). Our immune systems have adapted to these viruses and are usually able to handle infection with mild to no symptoms. Seasonality has been observed for the 4 commonly-circulating CoVs (229E, HKU1, NL63, OC43), with the bulk of cases studied in the Michigan cohort observed in January and February. Seasonality may look different in the tropics. Since 2017, my research group (Don Milton’s Public Health Aerobiology, Virology, and Exhaled Biomarker Laboratory) has been studying respiratory infections in dormitory residents on our University of Maryland campus and have detected dozens of CoV infections, generally associated with mild (yet annoying) illness. And yet SARS-CoV-2 is the third CoV to arise in the last 18 years to cause substantial public health concern. SARS emerged in 2002, spreading across Southeast Asia with almost 800 deaths. MERS emerged in 2012 and has claimed over 800 lives in 27 countries with a case-fatality rate over 30%. At the time of this writing there have been over 6 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 (from SARS-CoV-2 infection) and 372,501 deaths. Graham et al., 2013 provides a simplified family tree for CoVs (Figure 2), situating the commonly circulating CoVs as distinct from SARS-CoV and MERS. The emerging infectious diseases that we continue to see across the globe, including Zika (cause of the 2015-2016 pandemic), Lyme disease, and novel, highly pathogenic influenza viruses are driven by spillover of virus from animals into humans. Cui et al. dig into the likely bat and rodent origins (as reservoir species for these CoVs) and the passage of the virus from these species to other, intermediate host species (e.g., dromedary camels for MERS), before penetrating human populations. In a prophetic publication from September, 2019, on the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic, Li et al. described the human interface with bats in Southern China and detection of bat CoV infections in humans. A 2018 publication from Wang et al. showed 2.7% of people living close to bat caves in Yunnan province China had antibodies to bat CoVs. This process of viral exchange between wildlife and humans, while perhaps inevitable given human coexistence and interaction with other species, can be influenced by the types of interactions we have, and is at least partially driven by human exploitation of planetary resources, land and animals. Live poultry markets have been implicated as a source of highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza virus that has killed about 60% of humans infected. Meanwhile the human use of influenza antivirals as a strategy for population treatment and disease control carries the risks of exposing waterfowl, the main reservoir for influenza virus, to antiviral residues contained in human waste water, thus increasing selective pressure for anti-viral resistance and promoting the generation of a superbug. And back to SARS-CoV-2, there is some early evidence that the pangolin (I see them as beautiful creatures, and my brother has awakened me to the fact that they are depicted in Pokémon’s Sandshrew, Figure 3) may have been the intermediate species between bats and humans. Despite pangolins being listed as “endangered or threatened with extinction” by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and an international trading ban, an illegal pangolin trade continues to proliferate. Human consumption of animals as food or medicine (pangolin scales are often used for medicinal purposes in Eastern medicine) leads us toward the introduction of viruses into human populations from zoonotic sources (and vice versa) that are new to our immune systems and for which we haven’t yet developed widespread population immunity. This could increase the risk of future pandemics as summarized eloquently by Isaac Lawrence in Stat. Which brings us to where we are right now with this COVID-19 pandemic. It is widely accepted that SARS-CoV-2 enters human cells through the ACE2 (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) receptor on human cells. We also know that ACE2 is expressed on many types of human tissue including the respiratory tract, heart, and GI tract. But how SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted by which people and under which environmental conditions is largely unknown. Why is it challenging to understand more about transmission? We would have to show that the virus was shed from one person, track the physical movement of the virus, confirm that it reached a vulnerable locus in a susceptible person, and confirm that this virus (or community of viruses transmitted inside a small respiratory aerosolized droplet or secretion – we believe that lots of viruses can be contained in a single aerosolized particle so that if such a particle is inhaled it packs the punch of lots of viruses) was responsible for initiating infection in the secondary case. In over 100 years of study on this topic for flu we have not been able to reach consensus on the relative importance of the various transmission modes. To do so for a virus that has emerged in the last several months is a hard ask. Let’s consider some current evidence for airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Infectious SARS-CoV-2 virus has been detected in the air (Ong et al., Liu et al., Santarpia et al., Chia et al.). Whether the source of this airborne virus is exhaled breath, as has been shown to be possible for the commonly circulating CoVs (Leung et al.), or resuspension from surfaces, is largely unknown. Our group is actively working on answering this question by measuring how much virus people with SARS-CoV-2 shed into their exhaled breath as fine particle aerosols that linger in the air for hours, and as larger droplets that settle more quickly. Indoor temperature and relative humidity play a role in the settling velocities of the particles that are exhaled. Yuguo Li and colleagues fairly convincingly implicated airborne transmission in a poorly ventilated restaurant in Guangzhou (Figure 4). The person in purple is the primary case, those in red are secondary cases attributed to the exposure at the restaurant, and those in gold were uninfected. Computational fluid dynamics shows that exhaled breath from the primary case was likely to reach the three tables at the back of the restaurant, mediated by the recirculating ceiling HVAC unit, at much greater concentration than for the other tables in the restaurant, corresponding to the tables where the secondary infections occurred. This isn’t the only epidemiologic study to implicate airborne transmission for CoVs. SARS-1 likely spread via airborne plumes in the Amoy Gardens high rise apartments in Hong Kong, and in an airplane. Our own lab has recently shown associations between low ventilation and acute respiratory infection risk. The typical COVID-19 case may not be shedding many infectious doses per hour. But a few supershedders (who shed larger quantities of virus) may be responsible for driving epidemics responsible for a disproportionate proportion of transmission events. But in the absence of being able to identify supershedders early in their infectious window, we are left with population disease control strategies that are clunkier and more disruptive than they perhaps could be in some idealistic future where we rapidly identify the most contagious individuals and isolate them. We have made it this far through physical distancing measures in the US. As the country begins to return to more normal economic function, I hope that we can be hypervigilant about maintaining safe distance from each other, wearing face masks, reducing contact time with one another, and considering our indoor air environment. By appropriately increasing ventilation we can also reduce exposure to airborne viruses. The AIHA has some great resources to help guide businesses in their own reopening.

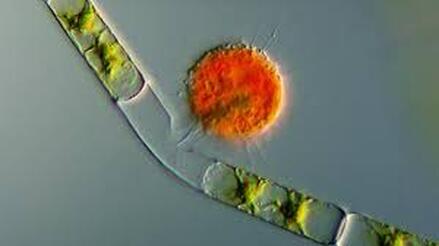

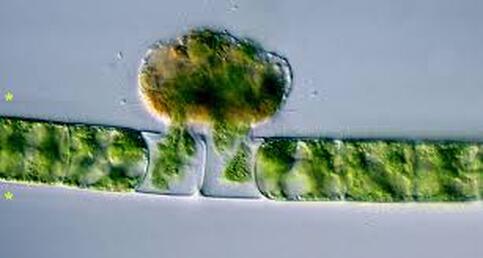

Most of all, I wish that we will care for each other better, love each other more, and be there for each other during this challenging time in our history. As recent events continue to highlight how the profound flaws in our nation’s fibers continue to deeply affect our fellow human family members of color and our entire community, any work for viral control must be rooted in a vibrant sense of care and love for those around us, especially communities of color. I’ll sign off with a musical exit assisted by MIT scientists who used the amino acids of CoV to create mesmerizing music. Here’s to unlocking more viral secrets so we can beat this pandemic and prevent or reduce the impact of those that may be on the horizon! References: References are provided as direct hyperlinks to sources throughout the post. by Ylenia Vimercati Molano A high diversity of endemic (found only in one place) microorganisms within the order Vampyrellida has been shown to dominate the eukaryotic microbial communities of ice and periglacial soils on the top of Mt. Kilimanjaro, the tallest free-standing mountain on Earth (Vimercati et al. 2019). The order Vampyrellida (Phylum Cercozoa) is a group of naked filose amoebae that forms distinctive morphologies, ultrastructure, and body forms (Gong et al. 2015). Also known as the “vampire amoebae”, these organisms have grabbed the attention of scientists since the early 1900s because of their unique mode of feeding on algae, fungal spores, and hyphae by cutting holes in the walls of the prey cells and sucking up the cytoplasm (Lloyd 1926, Figure 1, Figure 2). Seven genera of the order Vampyrellida have been described from aquatic and marine habitats and soils, where they prey on algae, fungi, protozoa, and small metazoans (Berney et al. 2013). It is also possible that this group of amoebae is associated with thermal environments with a continuous geothermal heat flux (Vimercati et al. 2019). Ice and periglacial soils from near the summit of Mt. Kilimanjaro (19,341 ft or 5,895 m above sea level) have shown to contain unexpectedly diverse and rich assemblages of Eukarya (Vimercati et al. 2019). The main drivers of microbial community composition at such high elevations are aerial deposition followed by post-depositional selection of organisms that can survive and reproduce in that particular environment (Xiang et al. 2009). The abundance of Vampyrellids observed in the study area can be explained by the fact that some Vampyrellida are very resistant to drought and are capable of responding rapidly to periods of transient nutrient and water availability (Berney et al. 2013). According to Hess et al. (2012), food preferences may also play an important role in lineage differentiation in Vampirellida. Within the order Vampyrellida, the most diversity on Mt. Kilimanjaro was found in the family Leptophryidae. Sanger sequencing, an older method of DNA sequencing that sequences longer strands of DNA, and phylogenetic analyses revealed how these organisms were clearly different from any other taxa in Genbank (a comprehensive database of organism DNA sequences) indicating that this peculiar environment hosts a previously unknown Vampyrellida community (Vimercati et al. 2019). The AMO has also described the presence of Vampyrellida in soils from the fumaroles (gas vents) on Volcán Socompa, a large stratovolcano at the border of Chile and Argentina (Schmidt et al. 2018). Interestingly, fumarolic activity is also present on Mt. Kilimanjaro. The fact that Mt. Kilimanjaro sequences were less than 95% identical to those from Volcán Socompa indicates a high endemicity of this group on the summit of Mt. Kilimanjaro (Vimercati et al. 2019). Ice and soil samples collected at the border of the plateau glacier in the Southern Ice Field showed that the relative abundance of the order Vampyrellida was significantly higher in the ice, indicating that the amoeba in the soil may have come from the ice (Vimercati et al. 2019). The presence of such eukaryotic diversity and endemism suggests that specific life forms have evolved to thrive in this extreme and isolated environment. On Mt. Kilimanjaro, larger eukaryotic microbes seem to be more dispersal limited compared to smaller organisms such as bacteria and archaea, and show distinct biogeographic patterns, as seen in the phylum Cercozoa, which showed a highly diverse new clade within the order Vampirellida (Vimercati et al. 2019).

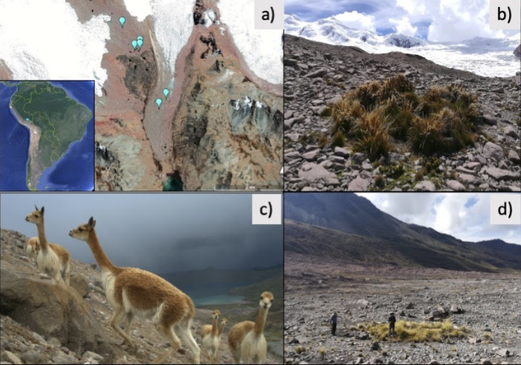

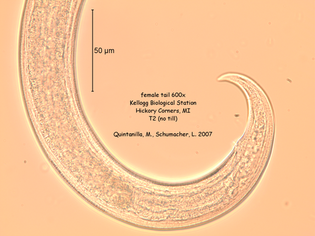

References: Berney C, Romac S, Mahé F, Santini S, Siano R, David B. (2013) Vampires in the oceans: predatory cercozoan amoebae in marine habitats. ISME J 7:2387–2399. Gong Y., Patterson D.J., Li Y., Hu Z., Sommerfeld M., Chen Y., Hu Q. (2015) Vernalophrys algivore gen. nov., sp. nov. (Rhizaria: Cercozoa: Vampyrellida), a new algal predator isolated from outdoor mass culture of Scenedesmus dimorphus. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:3900 –3913. Hess, S., Sausen, N. & Melkonian, M. (2012) Shedding light on vampires: the phylogeny of vampyrellid amoebae revisited. PLOS ONE 7(2), e31165. Lloyd FE. (1926) Some features of structure and behaviour in Vampyrella lateritia. Science 63:364–365. Schmidt, S. K. et al. (2018) Life at extreme elevations on Atacama volcanoes: the closest thing to Mars on Earth? Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 20, 1–3. Vimercati L, Darcy JL, Schmidt SK (2019) The disappearing periglacial ecosystem atop Mt. Kilimanjaro supports both cosmopolitan and endemic microbial communities. Scientific Reports 9:10676. By Cliff Bueno de Mesquita Hello everyone, we hope you all are doing well in these pandemic times. The lab is closed, and we are working from home, but there is plenty of data analysis and writing to do! Our collaborator Kelsey Reider, who has worked with us on projects in Perú, has recently been in touch and we are advancing manuscript preparation on our project looking at the effects of vicuña latrines on plant communities, microbial communities, soil nutrient concentrations, and soil temperatures. The idea is that these latrines are hotspots of nutrients in an otherwise severely nutrient-limited landscape (Darcy et al. 2018), and this could help plants establish on soils exposed by retreating glaciers (Figure 1). While glacier retreat is bad, it does open up some new habitat for plants, which is important because they may be losing habitat at lower elevations as they become too warm.  Figure 1. Photos of the field site and sampling locations. a) aerial photography of the rapidly retreating Puca Glacier and the locations of the six latrines sampled in this study. Inset shows the location in southeastern Peru. b) Photo of a latrine featuring dense plant growth, with the Puca Glacier in the background. c) A herd of vicuñas at the field site. d) Photo of SK Schmidt and CP Bueno de Mesquita in a latrine for scale. Photos by K. Reider. Vicuñas are abundant ungulates in the Andes Puna grasslands, and are traditionally herded for wool by native peoples of the region. An interesting feature of these animals is that groups of them defecate in the same place (Vilá 1994), leading to the creation of large piles of poop! In 2018 and 2019, we collected soils from such latrines and paired controls outside of the latrines. A nematode from the order Dorylaimida (Phylum = Nematoda, class = Enoplea), was found to be significantly more abundant in control soils compared to latrines, which suggests that they are able to tolerate nutrient poor conditions. Interestingly, they have also been noted as being able to eat cyanobacteria (Darby and Neher 2016), and there are higher relative abundances of cyanobacteria in the control soils. Unfortunately, with our 18S sequencing we could not resolve the taxonomy at a finer resolution. The order Dorylaimida contains free-living predaceous, plant-parasitic, ectoparasitic nematodes, and have been found in soils and freshwater habitats, where they can make up a significant part of the nematode biomass in these systems (Jairajpuri and Ahmad 1992). As predators, dorylaims attack and devour a range of small invertebrates (Poinjar Jr. 2015)! References:

Darby, B.J., & Neher, A. (2016). Microfauna within biological soil crusts. In Biological Soil Crusts: An Organizing Principle in Drylands. Weber, B., Büdel, B., and Belnap, J. (eds). Springer International Publishing Switzerland. Darcy, J. L., Schmidt, S. K., Knelman, J. E., Cleveland, C. C., Castle, S. C., & Nemergut, D. R. (2018). Phosphorus, not nitrogen, limits plants and microbial primary producers following glacial retreat. Science advances, 4(5), eaaq0942. Jairajpuri, M.S., & Ahmad, W. (1992). Dorylaimida: Free-living, Predaceous and Plant-parasitic nematodes. E.J. Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands. Poinjar Jr., G.O. (2015). Phylum Nemata. In Thorp and Covich’s Freshwater Invertebrates (4th Edition). https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/dorylaimida/pdf by Cliff Bueno de Mesquita Hello everyone, and happy leap year! We are excited to announce that we received a third year of funding from the Catto Foundation to study the effects of glyphosate herbicides on soil microbial communities here in Colorado prairies. I will share some information about another organism that responded to our nutrient and water amendment experiment on Volcán Llullaillaco in 2016. In addition to the Naganishia yeast, Dothideomycetes fungi, and Neochlorosarcina algae (see January post), we saw that Oxalobacteraceae within the Noviherbaspirillum genus significantly increased in soil microcosms with multiple water additions. The Oxalobacteraceae family is widespread in cryophilic and oligotrophic environments such as glacier-fed streams (Wilhelm et al. 2013), glacier forefields (Bajerski et al. 2013), cryoconites (Zhang et al. 2011) and high elevation periglacial soils (Vimercati et al. 2019). This family is metabolically diverse, and some genera are adapted to oligotrophic conditions (Baldani et al. 2014), which may allow them to use different aeolian deposited carbon sources. Some members of the Noviherbaspirillum genus have also been shown to be resistant to gamma radiation (Cheptsov et al. 2017) and close relatives of this OTU carry the nif genes (Baldani et al. 2014), which indicates that this OTU may make nitrogen available in this nutrient limited environment. Their lower relative abundance in soil microcosms that received both nutrient and water additions adds evidence for this group being oligotrophic and therefore being outcompeted by different phylotypes that show a faster response to carbon and nutrients alleviation. References:

Bajerski, F., Ganzert, L., Mangelsdorf, K., Lipski, A., Busse, H.J., Padur, L. and Wagner, D., 2013. Herbaspirillum psychrotolerans sp. nov., a member of the family Oxalobacteraceae from a glacier forefield. International journal of systematic and evolutionary microbiology, 63(9), pp.3197-3203. Baldani, J.I., Rouws, L., Cruz, L.M., Olivares, F.L., Schmid, M. and Hartmann, A., 2014. The family Oxalobacteraceae. The Prokaryotes: Alphaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria, pp.919-974. Cheptsov, Vladimir S., Elena A. Vorobyova, Natalia A. Manucharova, Mikhail V. Gorlenko, Anatoli K. Pavlov, Maria A. Vdovina, Vladimir N. Lomasov, and Sergey A. Bulat. "100 kGy gamma-affected microbial communities within the ancient Arctic permafrost under simulated Martian conditions." Extremophiles 21, no. 6 (2017): 1057-1067. Sundararaman, A., Srinivasan, S., Lee, S. 2016. Noviherbaspirillum humi sp. nov., isolated from soil. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 109, 697-704. Vimercati L., Solon, A.J., Krinsky, A., Arán, P., Porazinska, D.L., Darcy, J.L., Dorador, C., Schmidt, S.K. 2019. Nieves penitentes are a new habitat for snow algae in one of the most extreme high-elevation environments on Earth. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/15230430.2019.1618115 Wilhelm, L., Singer, G.A., Fasching, C., Battin, T.J. and Besemer, K., 2013. Microbial biodiversity in glacier-fed streams. The ISME journal, 7(8), p.1651. Zhang, X., Ma, X., Wang, N. and Yao, T., 2009. New subgroup of Bacteroidetes and diverse microorganisms in Tibetan plateau glacial ice provide a biological record of environmental conditions. FEMS microbiology ecology, 67(1), pp.21-29. |

AuthorVarious lab members contribute to the MoM Blog Archives

October 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed