|

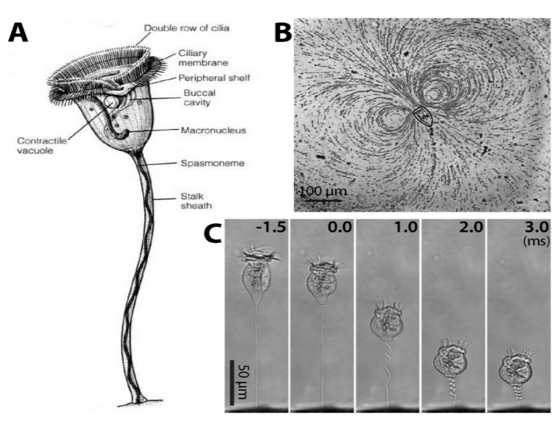

by Eli Gendron One of the greatest challenges sessile (immobile) organisms face is obtaining an adequate supply of food while not being able to actively forage or hunt for it. One way to get around this limitation is to have a motile life stage that is able to actively disperse to other parts of the environment where food might be more abundant (Sousa 1979). Members of the Vorticella genus are an example of ciliates that possess this adaptation, and thrive in a wide variety of freshwater habitats, and even inundated grasslands (Sun et al. 2012; Stout 1984). Ciliates are single-celled organisms that make up their own phylum (Ciliophora), and are characterized by having cilia, or hair-like structures on the outside of their cells. Vorticella species alternate between a free-swimming motile stage known as a telotroch, and a sessile phase known as a trophont, where it forms a contractible stalk that anchors the body to a substrate (Williams and Clamp 2007). The contractible stalk is one example how this genus has adapted to freshwater ecosystems. The stalk has been hypothesized to allow the body to retract closer to the substrate during turbulent conditions or potentially to mix its surroundings in order to obtain food in extremely calm conditions (Ryu et al. 2016, Figure1C). Vorticella sp. are very effective filter feeders (feeding by straining substances from the water) due to their ability to use their cilia to create currents that direct nearby organic matter directly into their body cavity (Ryu et al. 2016, Figure 1B). Taken together, these adaptations have made Vorticella sp. a target for bioengineering microfluidic devices. Outside of engineering applications Vorticella sp. even have potential applications as biocontrol agents for mosquitos. Patil et al. 2016 found that mosquito larvae that became infected with parasitic a Vorticella sp. saw a 90% reduction in adult emergence. Lastly, Vorticella’s ubiquity in freshwater habitats and their sensitivity to water quality make them excellent candidates for indicators of ecosystem health. For example, Vorticella sp. have been observed thriving in aquatic habitats with high levels of organic matter and low nitrogen cycling capacity (Perez-Uz et al. 2010).

References: Patil CD, Narkhede CP, Suryawanshi RK, Patil SV. 2016. Vorticella sp: Prospective mosquito biocontrol agent. J Arthropod Borne Dis 10:602–607. Pérez-Uz B, Arregui L, Calvo P, Salvadó H, Fernández N, Rodríguez E, Zornoza A, Serrano S. 2010. Assessment of plausible bioindicators for plant performance in advanced wastewater treatment systems. Water Res 44:5059–5069. Ryu S, Pepper RE, Nagai M, France DC. 2017. Vorticella: A protozoan for bio-inspired engineering. Micromachines 8:1–25. Stout JD. 1984. The protozoan fauna of a seasonally inundated soil under grassland. Soil Biol Biochem 16:121–125. Sun P, Clamp J, Xu D, Kusuoka Y, Miao W. 2012. Vorticella Linnaeus, 1767 (Ciliophora, Oligohymenophora, Peritrichia) is a Grade not a Clade: Redefinition of Vorticella and the Families Vorticellidae and Astylozoidae using Molecular Characters Derived from the Gene Coding for Small Subunit Ribosomal RN. Protist 163:129–142. Williams D, Clamp JC. 2007. A molecular phylogenetic investigation of Opisthonecta and related genera (Ciliophora, Peritrichia, Sessilida). J Eukaryot Microbiol 54:317–323.

0 Comments

|

AuthorVarious lab members contribute to the MoM Blog Archives

October 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed