|

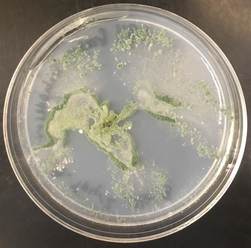

by Cliff Bueno de Mesquita I hope everyone had a wonderful Thanksgiving and gave thanks to all of the fascinating microorganisms that we depend on. For this post I’ll write about a fungus that I was recently able to culture (Figure 1). The green culture seen in Figure 1 is characteristic of the fungal genus Trichoderma. This culture was isolated from the inside of a root of a grass that I have been working with for the Moving Uphill project. I harvested the grasses that I transplanted into unvegetated soil 2 years ago to see what I could culture and isolate for potential follow up studies. Trichoderma is a ubiquitous soil fungus but recent studies have shown that it can also colonize plant roots (Harman et al. 2004, Bae et al. 2011). Trichoderma is in the Hypocreaceae family, in the Ascomycota phylum. The taxonomy has been updated several times, but there are currently 89 species recognized in the genus (Samuels 2006). Trichoderma viride, perhaps the species I have in culture, was the first species described in the genus and is a green mold. Trichoderma aggressivum is another green mold that causes disease on cultivated button mushrooms (Samuels et al. 2002). In soil, Trichoderma is a saprotroph, eating organic carbon in the form of dead plant and fungal material. Trichoderma produces enzymes to break this matter down, and humans have used Trichoderma to produce industrial amounts of decomposition enzymes like cellulase and chitinase (Felse and Panda 1999). Cellulase breaks down cellulose, the main ingredient of plant cell walls, while chitinase breaks down chitin, the main ingredient of fungal cell walls.

Inside of plant roots, the fungus produces a variety of compounds that can induce plant responses. Studies have shown that root colonization by Trichoderma frequently enhances root growth and development, plant productivity, resistance to abiotic stress, and nutrient uptake (Harman et al. 2004). Thus Trichoderma can be a very beneficial fungus for plants, but it has received much less attention than mycorrhizal fungi. It can be important for our crop plants too – Bae et al. (2011) found that Trichoderma helped delay disease in hot pepper plants. Perhaps it’s time for us to conduct some experiments with my cultures and see how they affect alpine plants! References: Bae, H; Roberts, DP; Lim, HS; Strem, MD; Park, SC; Ryu, CM; Melnick, RL; Bailey, BA (2011). Endophytic Trichoderma isolates from tropical environments delay disease onset and induce resistance against Phytophthora capsici in hot pepper using multiple mechanisms. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 24: 336–51. doi:10.1094/MPMI-09-10-0221. Felse, P.A, Panda, T. (1999). Taguchi Method. Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 40 (4): 801–805. doi:10.1016/j.enzmictec.2006.06.013. Harman, G.E., Howell, C.R., Viterbo, A., Chet, I., Lorito, M. (2004). Trichoderma species—opportunistic avirulent plant symbionts. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2 (1): 43–56. doi:10.1038/nrmicro797. Samuels, G.J., Dodd, S.L., Gams, W., Castlebury, L.A., Petrini, O. (2002). Trichoderma species associated with the green mold epidemic of commercially grown Agaricus bisporus. Mycologia. 94 (1): 146–170. Samuels, G.J. (2006). Trichoderma: Systematics, the Sexual State, and Ecology. Phytopathology. 96 (2): 195–206. doi:10.1094/PHYTO-96-0195.

0 Comments

|

AuthorVarious lab members contribute to the MoM Blog Archives

October 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed