|

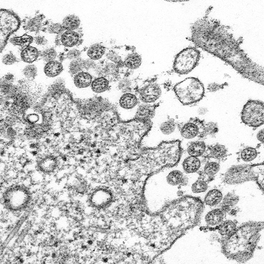

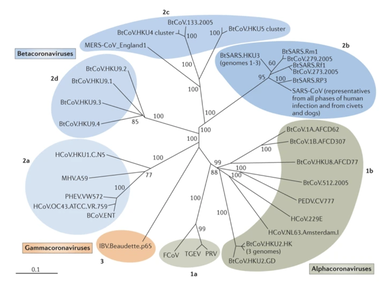

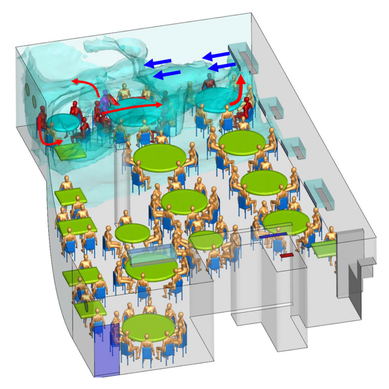

Written by Jacob Bueno de Mesquita Edited by Cliff Bueno de Mesquita For our first microbe of the month on viruses, we give a nod to the current microbial elephant in the room: the causative agent of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, SARS-CoV-2. The main bacterial and fungal players we commonly discuss here are actually much less “micro” than viruses. To give some perspective, a SARS-CoV-2 virion is about 0.12 µm (microns) in diameter, influenza viruses and adenoviruses are about 0.1, and rhinoviruses are about 0.03. A SARS-CoV-2 virion is about 250 times smaller than a human hair, and between 5 and 20 times smaller than an E. coli bacterium. One of the distinguishing characteristics of viruses from other microbes is that they are obligate parasites that rely entirely on hosts to produce proteins for self-assembly. In a sense, viruses could be considered non-living organisms. Perhaps we will dedicate a future post to discussion of the wonders and mysteries of the unique properties of viruses! SARS-CoV-2, like other coronaviruses (CoVs) has a spherical shape, with protein spikes that look like clubs covering its envelope outer surface. These characteristic spike proteins are what give CoVs their name, with some contending the spikes appear like a crown (corona in Latin, Figure 1). The spike protein acts as the virus’s “key” to enter animal host cells, acting as the receptor binding site. Because of its outward presentation and interaction with the host, this is also the protein used as a main target for the rapid vaccine development efforts underway across the globe. The SARS-CoV-2 genome has been studied with extensive phylogeny and transmission chain mapping (Nextstrain). Most virologists and public health experts express gratitude at the Chinese government’s rapid publishing of the genome sequence soon after initial cases emerged in Wuhan. CoVs have positive-sense, single-stranded RNA of 30 kilobases in a single strand (i.e. 30,000 base pairs). This contrasts with influenza viruses that have eight, segmented, negative-sense RNA strands and are more prone to mutation, resulting in the need for seasonal vaccines. Influenza genomic material can get exchanged between the segments when a host cell is infected with multiple viruses (reassortment) and this can lead to new viruses with pathogenic potential. This is one reason that influenza is the “common killer” in humans, remaining just out of the grasp of our ever-evolving immune responses. In contrast, CoVs do not mutate as rapidly, and are generally known for causing common colds. Humans have been carriers of CoVs for hundreds of years (perhaps even thousands). Our immune systems have adapted to these viruses and are usually able to handle infection with mild to no symptoms. Seasonality has been observed for the 4 commonly-circulating CoVs (229E, HKU1, NL63, OC43), with the bulk of cases studied in the Michigan cohort observed in January and February. Seasonality may look different in the tropics. Since 2017, my research group (Don Milton’s Public Health Aerobiology, Virology, and Exhaled Biomarker Laboratory) has been studying respiratory infections in dormitory residents on our University of Maryland campus and have detected dozens of CoV infections, generally associated with mild (yet annoying) illness. And yet SARS-CoV-2 is the third CoV to arise in the last 18 years to cause substantial public health concern. SARS emerged in 2002, spreading across Southeast Asia with almost 800 deaths. MERS emerged in 2012 and has claimed over 800 lives in 27 countries with a case-fatality rate over 30%. At the time of this writing there have been over 6 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 (from SARS-CoV-2 infection) and 372,501 deaths. Graham et al., 2013 provides a simplified family tree for CoVs (Figure 2), situating the commonly circulating CoVs as distinct from SARS-CoV and MERS. The emerging infectious diseases that we continue to see across the globe, including Zika (cause of the 2015-2016 pandemic), Lyme disease, and novel, highly pathogenic influenza viruses are driven by spillover of virus from animals into humans. Cui et al. dig into the likely bat and rodent origins (as reservoir species for these CoVs) and the passage of the virus from these species to other, intermediate host species (e.g., dromedary camels for MERS), before penetrating human populations. In a prophetic publication from September, 2019, on the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic, Li et al. described the human interface with bats in Southern China and detection of bat CoV infections in humans. A 2018 publication from Wang et al. showed 2.7% of people living close to bat caves in Yunnan province China had antibodies to bat CoVs. This process of viral exchange between wildlife and humans, while perhaps inevitable given human coexistence and interaction with other species, can be influenced by the types of interactions we have, and is at least partially driven by human exploitation of planetary resources, land and animals. Live poultry markets have been implicated as a source of highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza virus that has killed about 60% of humans infected. Meanwhile the human use of influenza antivirals as a strategy for population treatment and disease control carries the risks of exposing waterfowl, the main reservoir for influenza virus, to antiviral residues contained in human waste water, thus increasing selective pressure for anti-viral resistance and promoting the generation of a superbug. And back to SARS-CoV-2, there is some early evidence that the pangolin (I see them as beautiful creatures, and my brother has awakened me to the fact that they are depicted in Pokémon’s Sandshrew, Figure 3) may have been the intermediate species between bats and humans. Despite pangolins being listed as “endangered or threatened with extinction” by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and an international trading ban, an illegal pangolin trade continues to proliferate. Human consumption of animals as food or medicine (pangolin scales are often used for medicinal purposes in Eastern medicine) leads us toward the introduction of viruses into human populations from zoonotic sources (and vice versa) that are new to our immune systems and for which we haven’t yet developed widespread population immunity. This could increase the risk of future pandemics as summarized eloquently by Isaac Lawrence in Stat. Which brings us to where we are right now with this COVID-19 pandemic. It is widely accepted that SARS-CoV-2 enters human cells through the ACE2 (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) receptor on human cells. We also know that ACE2 is expressed on many types of human tissue including the respiratory tract, heart, and GI tract. But how SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted by which people and under which environmental conditions is largely unknown. Why is it challenging to understand more about transmission? We would have to show that the virus was shed from one person, track the physical movement of the virus, confirm that it reached a vulnerable locus in a susceptible person, and confirm that this virus (or community of viruses transmitted inside a small respiratory aerosolized droplet or secretion – we believe that lots of viruses can be contained in a single aerosolized particle so that if such a particle is inhaled it packs the punch of lots of viruses) was responsible for initiating infection in the secondary case. In over 100 years of study on this topic for flu we have not been able to reach consensus on the relative importance of the various transmission modes. To do so for a virus that has emerged in the last several months is a hard ask. Let’s consider some current evidence for airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Infectious SARS-CoV-2 virus has been detected in the air (Ong et al., Liu et al., Santarpia et al., Chia et al.). Whether the source of this airborne virus is exhaled breath, as has been shown to be possible for the commonly circulating CoVs (Leung et al.), or resuspension from surfaces, is largely unknown. Our group is actively working on answering this question by measuring how much virus people with SARS-CoV-2 shed into their exhaled breath as fine particle aerosols that linger in the air for hours, and as larger droplets that settle more quickly. Indoor temperature and relative humidity play a role in the settling velocities of the particles that are exhaled. Yuguo Li and colleagues fairly convincingly implicated airborne transmission in a poorly ventilated restaurant in Guangzhou (Figure 4). The person in purple is the primary case, those in red are secondary cases attributed to the exposure at the restaurant, and those in gold were uninfected. Computational fluid dynamics shows that exhaled breath from the primary case was likely to reach the three tables at the back of the restaurant, mediated by the recirculating ceiling HVAC unit, at much greater concentration than for the other tables in the restaurant, corresponding to the tables where the secondary infections occurred. This isn’t the only epidemiologic study to implicate airborne transmission for CoVs. SARS-1 likely spread via airborne plumes in the Amoy Gardens high rise apartments in Hong Kong, and in an airplane. Our own lab has recently shown associations between low ventilation and acute respiratory infection risk. The typical COVID-19 case may not be shedding many infectious doses per hour. But a few supershedders (who shed larger quantities of virus) may be responsible for driving epidemics responsible for a disproportionate proportion of transmission events. But in the absence of being able to identify supershedders early in their infectious window, we are left with population disease control strategies that are clunkier and more disruptive than they perhaps could be in some idealistic future where we rapidly identify the most contagious individuals and isolate them. We have made it this far through physical distancing measures in the US. As the country begins to return to more normal economic function, I hope that we can be hypervigilant about maintaining safe distance from each other, wearing face masks, reducing contact time with one another, and considering our indoor air environment. By appropriately increasing ventilation we can also reduce exposure to airborne viruses. The AIHA has some great resources to help guide businesses in their own reopening.

Most of all, I wish that we will care for each other better, love each other more, and be there for each other during this challenging time in our history. As recent events continue to highlight how the profound flaws in our nation’s fibers continue to deeply affect our fellow human family members of color and our entire community, any work for viral control must be rooted in a vibrant sense of care and love for those around us, especially communities of color. I’ll sign off with a musical exit assisted by MIT scientists who used the amino acids of CoV to create mesmerizing music. Here’s to unlocking more viral secrets so we can beat this pandemic and prevent or reduce the impact of those that may be on the horizon! References: References are provided as direct hyperlinks to sources throughout the post.

1 Comment

|

AuthorVarious lab members contribute to the MoM Blog Archives

October 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed