|

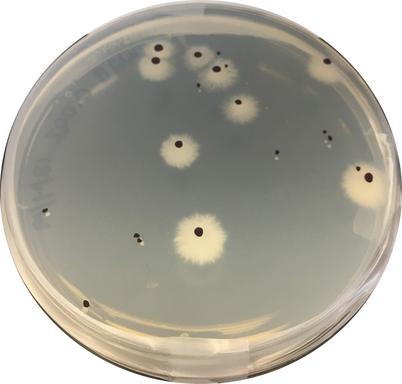

by Cliff Bueno de Mesquita Moesziomyces are one of the dominant soil fungi we found on Volcán Llullaillaco in the Atacama Desert in Chile, which is one of the most extreme environments on Earth. This high elevation site experiences high UV radiation, extreme diurnal freeze-thaw cycles, and is in the driest desert on Earth. It is possible that organisms here are dormant for most of the time but could become active during periodic snowfall events and aeolian deposition of dust containing small amounts of nutrients. In 2016, the AMO collected soils from this site and set up a microcosm experiment in a freeze-thaw chamber to assess water and nutrient limitations of the microbial community. DNA sequencing data showed that an OTU closely related to the fungal species Moesziomyces antarcticus (formerly Candida antarctica) significantly increased in relative abundance with multiple water additions to the microcosms, with the highest increase after the 3rd water addition. We just finished a follow up experiment plating these soils onto agar to grow colonies and count their abundances in the different water and nutrient additions. The plate count data corroborate the relative abundance sequencing data, showing dramatic increases in the number of colonies after 3 water additions and no nutrient additions. Species of Moesziomyces are known to produce both free-living saprobic anamorphs (yeast-like) and plant pathogenic teleomorphs (smuts) (Li et al. 2019). M. antarcticus was originally isolated from Antarctica and produces cold-active enzymes and biosurfactants (Perfumo et al. 2018). Biosurfactants have been shown to have different functions such as anti-agglomeration effects on ice particles (Perfumo et al. 2018) and are involved in cell adherence which imparts greatest stability under hostile environmental conditions. They can also be part of cellular envelopes and participate, together with other components such as exopolysaccharides, in protection against high salinity, temperature, and osmotic stress (Ewert and Deming 2013). Our study provides new evidence that along with its ability to withstand cold temperatures through cold adapted enzymes and other molecules, this yeast is also able to increase in abundance under extreme thermal fluctuations and very low nutrient contents.

References: Ewert, M. and Deming, J., 2013. Sea ice microorganisms: Environmental constraints and extracellular responses. Biology, 2(2), pp.603-628. Li, Y., Shivas, R.G., Li, B., and Cai, L., 2019. Diversity of Moesziomyces (Ustilaginales, Ustilaginomycotina) on Echinochloa and Leersia (Poaceae). MycoKeys, 52, doi:10.3897/mycokeys.52.30461. Perfumo, A., Banat, I.M. and Marchant, R., 2018. Going green and cold: biosurfactants from low-temperature environments to biotechnology applications. Trends in biotechnology, 36(3), pp.277-289.

0 Comments

|

AuthorVarious lab members contribute to the MoM Blog Archives

October 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed