|

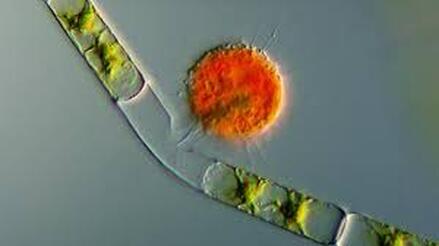

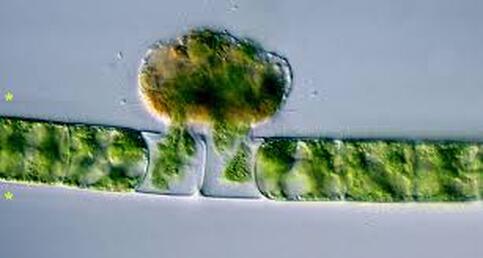

by Ylenia Vimercati Molano A high diversity of endemic (found only in one place) microorganisms within the order Vampyrellida has been shown to dominate the eukaryotic microbial communities of ice and periglacial soils on the top of Mt. Kilimanjaro, the tallest free-standing mountain on Earth (Vimercati et al. 2019). The order Vampyrellida (Phylum Cercozoa) is a group of naked filose amoebae that forms distinctive morphologies, ultrastructure, and body forms (Gong et al. 2015). Also known as the “vampire amoebae”, these organisms have grabbed the attention of scientists since the early 1900s because of their unique mode of feeding on algae, fungal spores, and hyphae by cutting holes in the walls of the prey cells and sucking up the cytoplasm (Lloyd 1926, Figure 1, Figure 2). Seven genera of the order Vampyrellida have been described from aquatic and marine habitats and soils, where they prey on algae, fungi, protozoa, and small metazoans (Berney et al. 2013). It is also possible that this group of amoebae is associated with thermal environments with a continuous geothermal heat flux (Vimercati et al. 2019). Ice and periglacial soils from near the summit of Mt. Kilimanjaro (19,341 ft or 5,895 m above sea level) have shown to contain unexpectedly diverse and rich assemblages of Eukarya (Vimercati et al. 2019). The main drivers of microbial community composition at such high elevations are aerial deposition followed by post-depositional selection of organisms that can survive and reproduce in that particular environment (Xiang et al. 2009). The abundance of Vampyrellids observed in the study area can be explained by the fact that some Vampyrellida are very resistant to drought and are capable of responding rapidly to periods of transient nutrient and water availability (Berney et al. 2013). According to Hess et al. (2012), food preferences may also play an important role in lineage differentiation in Vampirellida. Within the order Vampyrellida, the most diversity on Mt. Kilimanjaro was found in the family Leptophryidae. Sanger sequencing, an older method of DNA sequencing that sequences longer strands of DNA, and phylogenetic analyses revealed how these organisms were clearly different from any other taxa in Genbank (a comprehensive database of organism DNA sequences) indicating that this peculiar environment hosts a previously unknown Vampyrellida community (Vimercati et al. 2019). The AMO has also described the presence of Vampyrellida in soils from the fumaroles (gas vents) on Volcán Socompa, a large stratovolcano at the border of Chile and Argentina (Schmidt et al. 2018). Interestingly, fumarolic activity is also present on Mt. Kilimanjaro. The fact that Mt. Kilimanjaro sequences were less than 95% identical to those from Volcán Socompa indicates a high endemicity of this group on the summit of Mt. Kilimanjaro (Vimercati et al. 2019). Ice and soil samples collected at the border of the plateau glacier in the Southern Ice Field showed that the relative abundance of the order Vampyrellida was significantly higher in the ice, indicating that the amoeba in the soil may have come from the ice (Vimercati et al. 2019). The presence of such eukaryotic diversity and endemism suggests that specific life forms have evolved to thrive in this extreme and isolated environment. On Mt. Kilimanjaro, larger eukaryotic microbes seem to be more dispersal limited compared to smaller organisms such as bacteria and archaea, and show distinct biogeographic patterns, as seen in the phylum Cercozoa, which showed a highly diverse new clade within the order Vampirellida (Vimercati et al. 2019).

References: Berney C, Romac S, Mahé F, Santini S, Siano R, David B. (2013) Vampires in the oceans: predatory cercozoan amoebae in marine habitats. ISME J 7:2387–2399. Gong Y., Patterson D.J., Li Y., Hu Z., Sommerfeld M., Chen Y., Hu Q. (2015) Vernalophrys algivore gen. nov., sp. nov. (Rhizaria: Cercozoa: Vampyrellida), a new algal predator isolated from outdoor mass culture of Scenedesmus dimorphus. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:3900 –3913. Hess, S., Sausen, N. & Melkonian, M. (2012) Shedding light on vampires: the phylogeny of vampyrellid amoebae revisited. PLOS ONE 7(2), e31165. Lloyd FE. (1926) Some features of structure and behaviour in Vampyrella lateritia. Science 63:364–365. Schmidt, S. K. et al. (2018) Life at extreme elevations on Atacama volcanoes: the closest thing to Mars on Earth? Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 20, 1–3. Vimercati L, Darcy JL, Schmidt SK (2019) The disappearing periglacial ecosystem atop Mt. Kilimanjaro supports both cosmopolitan and endemic microbial communities. Scientific Reports 9:10676.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorVarious lab members contribute to the MoM Blog Archives

October 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed